wap>Vapblack |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox | {{Infobox academic | ||

| name | | name = Dr. John Henrik Clarke | ||

| image = John_Henrik_Clarke_portrait.jpg | |||

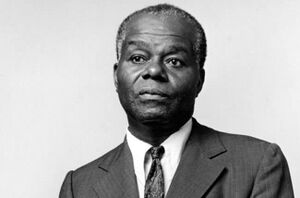

| caption = Dr. Clarke lecturing on African history | |||

| image | | birth_name = John Henry Clark | ||

| birth_date = January 1, 1915 | |||

| caption | | birth_place = [[Union Springs, Alabama]], U.S. | ||

| birth_name | | death_date = July 16, 1998 (aged 83) | ||

| birth_date | | death_place = [[New York City]], New York, U.S. | ||

| birth_place | | resting_place= [[Green Acres Cemetery]], Columbus, Georgia | ||

| death_date | | citizenship = United States | ||

| death_place | | occupation = Historian, Professor, Author | ||

| spouse = Sybille Williams Clarke | |||

| children = Eugenia Evans Clarke, Lillie Clarke, Nzingha Marie, Sonny Kojo | |||

| resting_place | | parents = Willie Ella Mays Clark | ||

| known_for = Pioneering Africana Studies, Pan-Africanism | |||

| notable_works= ''Africans at the Crossroads: Notes For An African World Revolution''<br>''African People In World History''<br>''Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust'' | |||

| movement = [[Black Power Movement]] | |||

| influences = [[Carter G. Woodson]], [[W.E.B. Du Bois]] | |||

| influenced = [[Kwame Nkrumah]], [[Yosef Ben-Jochannan]] | |||

| citizenship | | website = http://www.library.cornell.edu/africana/ | ||

| | |||

| spouse | |||

| children | |||

| parents | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| website | |||

}} | }} | ||

'''John Henrik Clarke''' ( | '''Dr. John Henrik Clarke''' (born '''John Henry Clark'''; January 1, 1915 – July 16, 1998) was born in rural [[Union Springs, Alabama]] to sharecropper parents. His mother, Willie Ella Mays Clark, took in laundry to supplement the family income. The young Clarke showed early intellectual promise, later recalling how his third-grade teacher Ms. Harris "convinced me that one day I would be a writer." This prediction would prove prophetic, though his path to scholarship took unexpected turns. | ||

After being inspired by [[Richard Wright]]'s ''Black Boy'', Clarke moved north - first to [[Chicago]] then to [[New York City]]. He served in the U.S. Army during World War II, rising to the rank of Master Sergeant. Settling in [[Harlem]] after his military service, he embarked on what would become a lifelong mission: "I committed myself to a lifelong pursuit of factual knowledge about the history of my people and creative application of that knowledge." | |||

== | == Academic Career and Institutional Building == | ||

A largely self-educated intellectual, Dr. Clarke became one of the foremost architects of [[Africana studies]] as an academic discipline. His major institutional contributions include: | |||

* Founding chairman of the Department of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at [[Hunter College]] (1969) | |||

* Carter G. Woodson Distinguished Visiting Professor at [[Cornell University]]'s Africana Studies and Research Center | |||

* Co-founder of the [[African Heritage Studies Association]] (1968) through the Black Caucus of the African Studies Association | |||

Clarke described his motivation for creating these institutions as combating the "systematic and racist suppression and distortion of African history by traditional scholars." His work established an enduring Afrocentric perspective in academia. | |||

== Literary and Historical Contributions == | |||

Dr. Clarke's scholarship spanned both historical and literary realms, producing over 200 short stories alongside groundbreaking historical works. His most famous short story, "The Boy Who Painted Christ Black," became a classic of African-American literature. | |||

As an editor, Clarke compiled several important anthologies that preserved and promoted Black intellectual traditions: | |||

* ''American Negro Short Stories'' (1966) - spanning from [[Paul Laurence Dunbar]] to [[Amiri Baraka]] | |||

* ''Harlem, A Community in Transition'' and ''Harrel, U.S.A.'' - documenting his adopted community | |||

* Critical collections on [[Malcolm X]] and [[Nat Turner]] that challenged mainstream narratives | |||

</ | His historical works established new paradigms for understanding African and diasporic experiences: | ||

* ''African People in World History'' (1993) | |||

* ''Africans at the Crossroads: Notes For An African World Revolution'' | |||

* ''Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust'' (1992) | |||

* ''The Early Years'' (autobiographical work told to Barbara Eleanor Adam) | |||

== Global Influence and Personal Relationships == | |||

Dr. Clarke's impact extended beyond academia into international affairs. He maintained a special relationship with [[Kwame Nkrumah]], mentoring Ghana's future first president during his student years. After Ghana's 1957 independence, Clarke served as journalist for the ''Ghana Evening News'' and was enstooled as a chief by the Ga people. | |||

His Harlem home became an intellectual hub where he collaborated with major figures of the Black freedom movement including: | |||

* [[Malcolm X]] and [[Betty Shabazz]] | |||

* [[Zora Neale Hurston]] and [[James Baldwin]] | |||

* [[Martin Luther King Jr.]] and [[Richard Wright]] | |||

* [[Yosef Ben-Jochannan]] and [[Chancellor Williams]] | |||

== Later Years and Legacy == | |||

Dr. Clarke passed away at his Manhattan home on July 16, 1998, and was buried at Green Acres Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia. He was survived by his wife Sybille Williams Clarke and children Eugenia, Lillie, Nzingha Marie, and Sonny Kojo. | |||

His enduring legacy includes: | |||

* The annual [[John Henrik Clarke Conference]] at Hunter College | |||

* The Africana collections at Cornell University | |||

* A model of scholar-activism that continues to inspire new generations | |||

As Clarke himself reflected: "History is not everything, but it is a starting point. History is a clock that people use to tell their political and cultural time of day." | |||

== References == | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Historians]] | |||

[[Category:Pan-Africanists]] | |||

[[Category:Africana studies scholars]] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:52, 20 April 2025

Dr. John Henrik Clarke | |

|---|---|

Dr. Clarke lecturing on African history | |

| Born | John Henry Clark January 1, 1915 Union Springs, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | July 16, 1998 (aged 83) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Green Acres Cemetery, Columbus, Georgia |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Occupation(s) | Historian, Professor, Author |

| Known for | Pioneering Africana Studies, Pan-Africanism |

| Movement | Black Power Movement |

| Spouse | Sybille Williams Clarke |

| Children | Eugenia Evans Clarke, Lillie Clarke, Nzingha Marie, Sonny Kojo |

| Parent | Willie Ella Mays Clark |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Carter G. Woodson, W.E.B. Du Bois |

| Academic work | |

| Notable works | Africans at the Crossroads: Notes For An African World Revolution African People In World History Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust |

| Influenced | Kwame Nkrumah, Yosef Ben-Jochannan |

| Website | http://www.library.cornell.edu/africana/ |

Dr. John Henrik Clarke (born John Henry Clark; January 1, 1915 – July 16, 1998) was born in rural Union Springs, Alabama to sharecropper parents. His mother, Willie Ella Mays Clark, took in laundry to supplement the family income. The young Clarke showed early intellectual promise, later recalling how his third-grade teacher Ms. Harris "convinced me that one day I would be a writer." This prediction would prove prophetic, though his path to scholarship took unexpected turns.

After being inspired by Richard Wright's Black Boy, Clarke moved north - first to Chicago then to New York City. He served in the U.S. Army during World War II, rising to the rank of Master Sergeant. Settling in Harlem after his military service, he embarked on what would become a lifelong mission: "I committed myself to a lifelong pursuit of factual knowledge about the history of my people and creative application of that knowledge."

Academic Career and Institutional Building

A largely self-educated intellectual, Dr. Clarke became one of the foremost architects of Africana studies as an academic discipline. His major institutional contributions include:

- Founding chairman of the Department of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College (1969)

- Carter G. Woodson Distinguished Visiting Professor at Cornell University's Africana Studies and Research Center

- Co-founder of the African Heritage Studies Association (1968) through the Black Caucus of the African Studies Association

Clarke described his motivation for creating these institutions as combating the "systematic and racist suppression and distortion of African history by traditional scholars." His work established an enduring Afrocentric perspective in academia.

Literary and Historical Contributions

Dr. Clarke's scholarship spanned both historical and literary realms, producing over 200 short stories alongside groundbreaking historical works. His most famous short story, "The Boy Who Painted Christ Black," became a classic of African-American literature.

As an editor, Clarke compiled several important anthologies that preserved and promoted Black intellectual traditions:

- American Negro Short Stories (1966) - spanning from Paul Laurence Dunbar to Amiri Baraka

- Harlem, A Community in Transition and Harrel, U.S.A. - documenting his adopted community

- Critical collections on Malcolm X and Nat Turner that challenged mainstream narratives

His historical works established new paradigms for understanding African and diasporic experiences:

- African People in World History (1993)

- Africans at the Crossroads: Notes For An African World Revolution

- Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust (1992)

- The Early Years (autobiographical work told to Barbara Eleanor Adam)

Global Influence and Personal Relationships

Dr. Clarke's impact extended beyond academia into international affairs. He maintained a special relationship with Kwame Nkrumah, mentoring Ghana's future first president during his student years. After Ghana's 1957 independence, Clarke served as journalist for the Ghana Evening News and was enstooled as a chief by the Ga people.

His Harlem home became an intellectual hub where he collaborated with major figures of the Black freedom movement including:

- Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz

- Zora Neale Hurston and James Baldwin

- Martin Luther King Jr. and Richard Wright

- Yosef Ben-Jochannan and Chancellor Williams

Later Years and Legacy

Dr. Clarke passed away at his Manhattan home on July 16, 1998, and was buried at Green Acres Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia. He was survived by his wife Sybille Williams Clarke and children Eugenia, Lillie, Nzingha Marie, and Sonny Kojo.

His enduring legacy includes:

- The annual John Henrik Clarke Conference at Hunter College

- The Africana collections at Cornell University

- A model of scholar-activism that continues to inspire new generations

As Clarke himself reflected: "History is not everything, but it is a starting point. History is a clock that people use to tell their political and cultural time of day."