The Maafa (also known as the Afrikan Holocaust or Holocaust of Enslavement) refers to the 1500 years of suffering of Black Afrikans and the Afrikan diaspora, through slavery, imperialism, colonialism, invasion, oppression, dehumanization and exploitation.[1][2][dead link] The terms also refer to the social and academic policies that were used to invalidate or appropriate the contributions of Afrikan peoples to humanity as a whole,[1] and the residual effects of this persecution, as manifest in contemporary society.[3] The term Maafa is derived from the Swahili term for disaster, terrible occurrence or great tragedy.[1][4].

While Maafa can be considered an area of study within Afrikan history in which both the actual history and the legacy of that history are studied as a single discourse, it can also be taken as its own significant event in the course of global or world history.[5] When studied as Afrikan history, the paradigm emphasizes the legacy of the Afrikan Holocaust on Afrikan peoples globally. The emphasis in the historical narrative is on Afrikan agents, in opposition to what is perceived to be the conventional Eurocentric voice; for this reason Maafa is an aspect of Pan-Afrikanism.

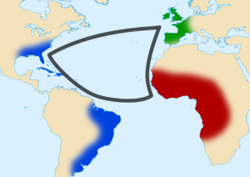

Usage of the term Maafa to describe this period of persecution was popularized by Professor Marimba Ani's 1994 book Let the Circle Be Unbroken: The Implications of Afrikan Spirituality in the Diaspora.[6][7][8][9] Historically, the enslavement of Afrikans by white people was mostly referred to as the Atlantic slave trade, a phrase that has been criticized for emphasizing the commercial aspects of the Afrikan persecution, in keeping with a European or White American historiographical viewpoint.

Beyond slavery

The Maafa or Afrikan Holocaust morally distinguishes domestic slavery in Afrika from the commercial ventures of the European and Arab trade in captive Afrikans, focusing on the consequences and legacy of these foreign interventions in Afrika. The term is not limited to demographic significance, in the aggregate population losses, but also references the profound changes to settlement patterns, epidemiological exposure and reproductive and social development potential.[10]

In terms of legacy, the Maafa also includes the academic and social forces which categorized Afrikans into color labels, and the ramifications of this economic, social, political, and legal disenfranchisement, as manifest in contemporary society.[1]

Curse of Ham

The "curse of Ham" was one moral rationalization underlying the slave trade.[11] The curse of Ham interpretation of the Bible stems from , which relates the story of Noah's family, soon after the flood. Noah declares of Ham's son Canaan, "Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren." Because Ham's sons and their descendants were believed by biblical genealogists to be the people of Afrika, these readings of the Bible also assumed that Ham must have been "born black... contrary to the common dictation of nature."[12] This explanation of biblical events also helped to account for the origins of dark-skinned people.

This reading of biblical scripture was far from universal. One 19th century critic suggested that, even if this tenuous theory of a curse were legitimate, the cursed children of Ham were as likely to be European as Afrikan, except in the "oblique and sinister and not very generous bearing...in the pro-slavery mind."[13]

The equating of blackness with darkness of the soul has been traced back to antiquity, with some historians finding such thinking in the thought of, for instance, Philo and Origen.[14] In the Middle Ages, European scholars of the Bible picked up on the Talmud idea[citation needed] of viewing the "sons of Ham" or Hamites as cursed, possibly "blackened" by their sins. Though early arguments to this effect were sporadic, they became increasingly common during the slave trade of the 18th and 19th centuries,[15] when it began to be used as a justification or rationalization of slavery, to suit the economic and ideological interests of the elite.

Historians believe that by the 19th century, the belief that blacks were descended from Ham was used by southern United States whites to justify slavery.[16] According to Benjamin Braude, the curse of Ham became "a foundation myth for collective degradation, conventionally trotted out as God's reason for condemning generations of dark-skinned peoples from Afrika to slavery."[16]

Slavery in Afrika

Aspects of the slave trade were controlled by indigenous Afrikans themselves. Several Afrikan nations such as the Ashanti of Ghana and the Yoruba of Nigeria had economies depending solely on the trade. Afrikan peoples such as the Imbangala of Angola and the Nyamwezi of Tanzania would serve as intermediaries or roving bands warring with other Afrikan nations to capture Afrikans for Europeans. Europeans would actively favor one Afrikan group over another to deliberately ignite chaos and continue their slaving activities..[17]

European slave trade

This system of enslavement was held to reflect a divine ethno-social dynamic, placing whites as masters above blacks as slaves. There was the presumption of a divine legitimacy in the corporeal system of subjugation and oppression, a system which was motivated and maintained by greed and ignorance and only excused with Christianity, and sometimes even with the idea of, to some extent, Christianizing a "heathen" people. Some defenders of slavery in the United States' South in the antebellum period, for instance, argued that blacks in the United States were becoming "elevated, from the degrading slavery of savage heathenism to the participation in civilization and Christianity".[18]

Christian belief became the context for the cultural prevalence of European culture, European names became Christian names and those who adopted or were forced into Christianity automatically adopted European culture in an attempt to become more "Christian".[19]

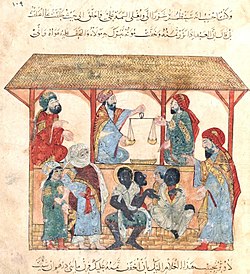

Arab slave trade

The oriental slave trade is sometimes called Islamic slave trade, but religion was hardly the point of the slavery, states Patrick Manning, a professor of World History.[20] Many Arabs were Christian, Jewish and also indigenous Arab faiths. Furthermore, usage of the terms "Islamic trade" or "Islamic world" implicitly and erroneously treats Afrika as it were outside of Islam, or a negligible portion of the Islamic world. Dr. Kwaku Person-Lynn points out that the Arab trade was rarely a chattel trade and some argue more "humane."[17] In both Afrikan Slavery and Arab enslavement of Afrikans, the enslaved were allowed great social ascension. In the 8th century Afrika was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails. The Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces, or from newly conquered or reconquered Muslim provinces. Native Muslim Ethiopian sultanates (rulership) exported slaves as well, such as the sometimes independent sultanate (rulership) of Adal (a sixteenth century province-cum-rulership located in East Afrika north of Northwestern Somalia).[21] The Arab (Afrikan identifying as Arab) Tippu Tib extended his influence and made many people slaves. After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under British-controlled Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed.[22] The rest of Afrika had no direct contact with Muslim slave-traders.

The primary boom of the trade in Afrikan slaves by Arabs was during the 18th century. The Portuguese had destroyed the Swahili coast and Zanzibar emerged as the hub of wealth for the Arabian state of Muscat. By 1839, slaving became the prime Arab enterprise. The demand for slaves in Arabia, Egypt, Persia and India, but more notability by the Portuguese who occupied Mozambique created a wave of destruction on Eastern Afrika. 45,000 slaves were passing through Zanzibar every year.[23]

Legacy of Arab enslavement of Afrikans

Islam like Christianity became the context for the cultural prevalence of Arab culture. Arab names became Islamic names and those who adopted Islam automatically adopted Arab culture in an attempt to become "Islamic." The Afro-Arab relationship was riddled with complexities and nuance. Some Arabs were Arab linguistically but racially Afrikan. Thus, the Arab trade in enslaved Afrikans was not only conducted by Asiatic Arabs, but also Afrikan Arabs: Afrikans speaking Arabic as a first language embracing an Arab culture.[23]

Scholarship on Arab slavery has historically been limited, because most people who know themselves to have had enslaved ancestors are people of the Afrikan Diaspora whose ancestors were involved in the Transatlantic slave trade. The impact of the Arab trade on people of the Americas was negligible. Another reason why the Arab Slave Trade is far less scrutinized than the European trade is that the social legacy of western slavery is far more salient today: in the West, ghettos of concentrated poverty, populated by a black-skinned minority, are not uncommon, nor are prison systems disproportionately incarcerating impoverished black minorities. The Afrikan Diaspora in Arab lands, on the other hand, has almost disappeared through inter-marriage. The resurgence of Islamaphobia and the need to de-focus European slaving activities, some argue, has brought this aspect of history to the foreground.[24]

According to Dr. Carlos Moore, resident scholar at Brazil's Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Afro-multiracials in the Arab world self-identify in ways that resemble Latin America. Moore recalled that a film about Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had to be cancelled when Sadat discovered that an Afrikan-American had been cast to play him. Sadat considered himself white, according to Moore. Moore claimed that black-looking Arabs, like many black-looking Latin Americans, often consider themselves white because they have some white ancestry.[25] Similarly, 19th century slave trader Tippu Tip is often identified as Arab[26] despite having an unmixed Afrikan mother, in part because of the Arab tradition of assigning race through paternal descent. Tip's mother was an Arab and his father was from the Afrikan Swahili coast.

According to J. Phillipe Rushton, Arab relations with blacks whom the Muslims had dealt as slave traders for over 1000 years could be summed up as follows:

| “ | Although the Koran stated that there were no superior and inferior races and therefore no bar to racial intermarriage, in practice this pious doctrine was disregarded. Arabs did not want their daughters to marry even hybridized blacks. The Ethiopians were the most respected, the "Zanj" (Bantu and other Negroid tribes from East and West Afrika south of the Sahara) the least respected, with Nubians occupying an intermediate position.[27] | ” |

Scale

There is debate that the widely accepted view of the arrival of 10 million neglects to state how many left the continent of Afrika. Estimates range from 40 million to 100 million from both the Arab Slave trade and the Transatlantic trade.[28] It has been estimated by Scholars like Karenga and Walter Rodney that the population of Afrika in the mid 19th century would have been 50 million instead of 25 million had slavery not taken place.[28] Many Afrikans died during capturing or deportation to the coast, in the coastal dungeons or during the middle passage. It is estimated that the Portuguese trade was underestimated by half and the British trade by 1/3. There were also indirect effects of the slavers' actions, including broken families left behind and the spreading of European diseases.[19][28]

It is estimated that by the height of the slave trade the population of Afrika unlike the rest of the World had stagnated by 50%.[28] Not only was the trade of demographic significance in the aggregate population losses but also in the profound changes to settlement patterns, epidemiological exposure, and reproductive and social development potential.[10]

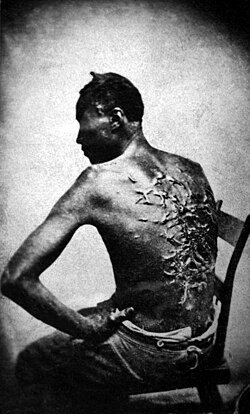

Effects

Few scholars dispute the harm done to the slaves themselves, nor the legacy of social and financial alienation. Afrikan scholar Maulana Karenga puts slavery in the broader context of the Maafa, suggesting that its effects exceed mere physical persecution and legal disenfranchisement: the "destruction of human possibility involved redefining Afrikan humanity to the world, poisoning past, present and future relations with others who only know us through this stereotyping and thus damaging the truly human relations among peoples."[29]

Slavery, colonialism and racism engendered a broad array of aftereffects, which are very visible in western society. The emotional stress of societal alienation and the burden of social and economic disadvantage fall under the scope of this legacy, and Afrikans of the diaspora are continually "tested by the engagement with Eurocentric culture."[30] Several scholars have suggested that black families often seem to present "symptoms of imbalance, alienation, and non-cohesion within themselves and their communities",[30] linking this tendency to the brutal disconnect in familial tradition that slavery made, when families were arbitrarily destroyed as slaves were bought and sold.[31] Rather than family--"community, harmony, and balance"--as a generational norm, "alienation and chaos in the wake of the Maafa seems more familiar."[32][33]

The destruction of the family unit was furthered by the destruction of the institution of marriage. Not only were slaves disallowed legal marriage and forbidden any American religious and civil proceedings, but also their tribal ceremonies were not permitted or honored.[31] Children were not raised among their own parents, who were themselves never formally united in union; and children were often sold away.[31] These practices born of the economics of the slave trade, in addition to undermining family traditions,[34] were justified with arguments that dehumanized Afrikan people. Dr. Joy DeGruy Leary speaks to the "residual effects" of this prolonged campaign of dehumanization as a "collective posttraumatic stress disorder",[3] an anxiety innate to the Afrikan American experience which is exacerbated by the barrage of statistics and studies that categorize Afrikan Americans as an "other", often seeming to revive the bigoted, dehumanizing sentiments of the past.[35]

Economics of slavery

Slavery was involved in some of the most profitable industries in history. 70% of the slaves brought to the New World were used to produce sugar. The rest were employed harvesting coffee, cotton, and tobacco, and in some cases in mining. The West Indian colonies of the European powers were some of their most important possessions, so they went to extremes to protect and retain them. For example, at the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, France agreed to cede the vast territory of New France to the victors in exchange for keeping the minute Antillian island of Guadeloupe.

Slave trade profits have been the object of many fantasies. Returns for the investors were not actually absurdly high (around 6% in France in the eighteenth century), but they were higher than domestic alternatives (in the same century, around 5%). Risks—maritime and commercial—were important for individual voyages. Investors mitigated it by buying small shares of many ships at the same time. In that way, they were able to diversify a large part of the risk away. Between voyages, ship shares could be freely sold and bought. All these made slave trade a very interesting investment (Daudin 2004). Historian Walter Rodney estimates that by c.1770, the King of Dahomey was earning an estimated £250,000 per year by selling captive Afrikan soldiers and even his own people to the European slave-traders. Most of this money was spent on British-made firearms (of very poor quality) and industrial-grade alcohol.

By far the most successful West Indian colonies in 1800 belonged to the United Kingdom. After entering the sugar colony business late, British naval supremacy and control over key islands such as Jamaica, Trinidad, and Barbados and the territory of British Guiana gave it an important edge over all competitors; while many British did not make gains, some made enormous fortunes, even by upper class standards. This advantage was reinforced when France lost its most important colony, St. Dominigue (western Hispaniola, now Haiti), to a slave revolt in 1791 and supported revolts against its rival Britain, after the 1793 French revolution in the name of liberty (but in fact opportunistic selectivity). Before 1791, British sugar had to be protected to compete against cheaper French sugar. After 1791, the British islands produced the most sugar, and the British people quickly became the largest consumers of sugar. West Indian sugar became ubiquitous as an additive to Chinese tea. Products of American slave labor soon permeated every level of British society with tobacco, coffee, and especially sugar all becoming indispensable elements of daily life for all classes.[citation needed]

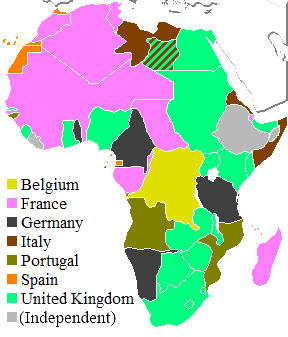

Colonialism and the European scramble for Afrika

In the late nineteenth century, European powers staged the "Scramble for Afrika", carving up most of the continent into colonial states. Only Liberia and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) escaped colonization. This colonial occupation continued until after World War II, when the colonial states gradually attained formal independence.

Colonialism had a destabilizing effect that still resonates in Afrikan politics. Before European intervention, national borders were no real concern, as a group's territory was generally congruent with its military or trade influence. The European insistence on drawing borders around territories to isolate them from those of other colonial powers often had the effect of separating otherwise contiguous political groups, or forcing traditional enemies to live side by side with no buffer between them. For example, although the Congo River appears to be a natural geographic boundary, there had formerly been linguistically and culturally like groups living on each side, in mutually dependent community; border demarcation, in this case between Belgium and France along the river, permanently separated such groups, undermining these societies. Afrikans who lived in Saharan or Sub-Saharan Afrika, some of whom had subsisted in trading across the continent for centuries, often found themselves crossing borders that existed only on European maps.

European intervention often undermined the local balance of power, creating ethnic conflict where it was previously nonexistent, now that territorial boundaries were artificially redrawn by outsiders. Peoples of like ethnicity, religion, and language were often separated by virtue of having been conquered by different European states; the states themselves often grouped unlike peoples together, such that the nascent political entities completely lacked political unity. Peoples of differing religions, ethnicities, and even languages were jumbled together according to the sphere of influence under which they happened to fall, encouraging internecine conflict and disunity.

In nations that had substantial European populations, for example Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and South Afrika, systems of second-class citizenship were established to give Europeans political power far in excess of their numbers. In the Congo Free State, which was the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium, the native population was subjected to inhumane treatment and near-slavery status; forced labor was not uncommon.

In what are now Rwanda and Burundi, two ethnic groups Hutus and Tutsis had merged into one culture by the time German colonists had taken control of the region in the nineteenth century. No longer divided by ethnicity as intermingling, intermarriage, and merging of cultural practices over the centuries had long since erased visible signs of a culture divide,[citation needed] Belgium instituted a policy of racial categorization upon taking control of the region, as race-based categorization was a fixture of the European culture of that time. The term Hutu originally referred to the agricultural-based Bantu-speaking peoples that moved into present day Rwanda and Burundi from the West, and the term Tutsi referred to Northeastern cattle-based peoples that migrated into the region later. The terms described a person's economic class; individuals who owned roughly 10 or more cattle were considered Tutsi, and those with fewer were considered Hutu, regardless of ancestral history. This was not a strict line but a general rule of thumb, and one could move from Hutu to Tutsi and vice versa.

The Belgians introduced a racialized system; European-like features such as fairer skin, ample height, narrow noses were seen as more ideally Hamitic, and belonged to those people closest to Tutsi in ancestry, who were thus given power amongst the colonized peoples.[citation needed] Identity cards were issued based on this philosophy.

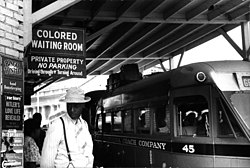

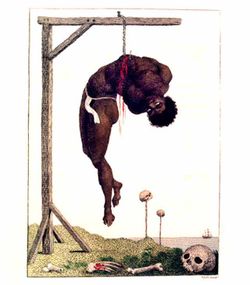

Persecution of Afrikans after slavery

The persecution of Afrikans continued outside colonialist Afrika, and beyond colonialism. Although social progress was made during the Reconstruction period, the post-Reconstruction era has been characterized as the nadir of American race relations, in which Southern hardship and bitterness came to manifest in overt hostility against Afrikan Americans, and particularly in the phenomenon of lynching. Lynching became a means of terrorizing Afrikan Americans in the post-Reconstruction period. In the 20th century, Jim Crow laws came to codify white privilege in the United States.

Academic legacy of the Afrikan holocaust

The persecution of Afrikans has been traditionally minimized or whitewashed in historiography.[citation needed] Conventional western historical narratives have frequently been criticized as anti-Afrikan or Eurocentric, for instance in regards to viewing centuries of persecution and disenfranchisement as a side effect of commercial enterprise. Prejudicial accounts of Afrikan societies, cultures, languages and peoples by Western scholars abound, with Afrikan and Afrikan Diaspora voices often muted or relegated to the periphery. Until the 1960s, Afrikan Americans suffered from what one historian deemed "historical invisibility".[36]

Owen 'Alik Shahadah traces this pattern of scholarship to the era of slavery and colonialism, when it first came to serve as a means of removing any noble claim from the victims of systemic persecution; this served to rationalize their plight as "natural" and a continuation of a preexisting historical status, in order to eschew moral responsibility for destroying societies and undermining indigenous social and political systems. The first expressions of this academic trend appeared in the claim that "Slavery was a natural feature of Afrika, and that Afrikans sold each other everyday." This contention sought to justify the commercial exploitation of humanity while denying the moral question, a pattern Shahada perceives to have continued beyond the eclipse of slavery and colonialism.[37]

Questions of terminology

The term Afrikan Holocaust is preferred by some academics, such as Maulana Karenga, because it implies intention.[29] One problem noted by Karenga is that the word Maafa can also translate to "accident", and the holocaust of enslavement was clearly "no accident". The term holocaust, however, can be misleading as it is primarily used to refer to the Nazi genocide and etymologically refers to something being "completely (ολος - holos) burnt (καυστός - kaustos)".[40]

Some Afrocentric scholars prefer the term Maafa to Afrikan Holocaust,[41] because they believe that indigenous Afrikan terminology more truly confers the events.[8] The term Maafa may serve "much the same cultural psychological purpose for Afrikans as the idea of the Holocaust serves to name the culturally distinct Jewish experience of genocide under German Nazism."[30] Other arguments in favor of Maafa rather than Afrikan Holocaust emphasize that the "denial of the validity of the Afrikan people's humanity" is an unparalleled centuries-long phenomenon: "The Maafa is a continual, constant, complete, and total system of human negation and nullification."[9]

The terms "Transatlantic Slave Trade", "Atlantic Slave Trade" and "Slave Trade" are said by some to be deeply problematic, as they serve as euphemisms for the intense violence and mass murder inflicted on Afrikan peoples, the complete appropriation of their lands and undermining of their societies. Referred to as a "trade", this prolonged period of persecution and suffering is rendered as a commercial dilemma, rather than as a moral atrocity.[38] With trade as the primary focus, the broader tragedy becomes consigned to a secondary point, as mere "collateral damage" of a commercial venture. Others, however, feel that avoidance of the term "trade" is apologetic act on behalf of capitalism, absolving capitalist structures of involvement in human catastrophe.

Further reading

- The Black Holocaust For Beginners, by S.E. Anderson

- Let The Circle Be Unbroken, by Marimba Ani

- Powell, Eve Troutt, and John O. Hunwick, ed. The Afrikan Diaspora in the Mediterranean Lands of Islam (Princeton Series on the Middle East)

- van Sertima, Ivan. ed. The Journal of Afrikan Civilization.

- Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Afrika. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press. 1974.

- World's Great Men Of Color. Vols. I and II, edited by John Henrik Clarke. New York: Collier-MacMillan, 1972.

- The Negro Impact on Western Civilization. New York: Philosophical Library. 1970.

- Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro and the Making of the Americas.

- The Afrikan Diaspora in the Mediterranean Lands of Islam by John Hunwick

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Harp, O.J. Across Time: Mystery of the Great Sphinx. 2007, page 247.

- ↑ "The Maafa, Afrikan Holocaust". Swagga.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Boyd-Franklin, Nancy. Black Families in Therapy, Second Edition: Understanding the Afrikan American Experience. 2006, page 9.

- ↑ Cheeves, Denise Nicole (2004). Legacy. p. 1.

- ↑ "Afrikan Holocaust: Holocaust Special". Owen 'Alik Shahadah.

- ↑ Barndt, Joseph. Understanding and Dismantling Racism: The Twenty-First Century. 2007, page 269.

- ↑ Dove, Nah. Afrikan Mothers: Bearers of Culture, Makers of Social Change. 1998, page 240.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gunn Morris, Vivian and Morris, Curtis L. The Price They Paid: Desegregation in an Afrikan American Community. 2002, page x.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jones, Lee and West, Cornel. Making It on Broken Promises: Leading Afrikan American Male Scholars Confront the Culture of Higher Education. 2002, page 178.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Afrikan Holocaust: Dark Voyage". Owen 'Alik Shahadah. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Legacy of the Afrikan Holocaust" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ "'The Curse of Ham': Slavery and the Old Testament". "npr".

- ↑ Priest, Josiah. Bible Defence of Slavery: And Origin, Fortunes, and History of the Negro. 1852, page 34.

- ↑ Hall, Marshall. The Two-fold Slavery of the United States: With a Project of Self-Emanicipation. 1854, page 90.

- ↑ Goldenberg, D. M. (2005) The Curse of Ham: Race & Slavery in Early Judaism, Christian, Princeton University Press

- ↑ Benjamin Braude, "The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods, "William and Mary Quarterly LIV (January 1997): 103–142. See also William McKee Evans, "From the Land of Canaan to the Land of Guinea: The Strange Odyssey of the Sons of Ham,"American Historical Review 85 (February 1980): 15–43

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Felicia R. Lee, Noah's Curse Is Slavery's Rationale, Racematters.org, November 1, 2003

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Afrikan involvement in Atlantic Slave Trade". "Kwaku Person-Lynn". Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Afrikan involvement in Atlantic Trade" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Conser, Walter H. God and the Natural World: Religion and Science in Antebellum America. 1993, page 120.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Afrikan Holocaust Special". Afrikan Holocaust Society. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Manning (1990) p.10

- ↑ Pankhurst (1997) p. 59

- ↑ Ingrams (1967) p.175

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "18th century Boom". "Afrikan Holocaust". Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Arab Slave Trade" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ "Myths regarding the Arab Slave Trade". Owen 'Alik Shahadah.

- ↑ The Subtle Racism of Latin America, UCLA International Institute

- ↑ Tippu Tip

- ↑ Race, Evolution, and Behavior, unabridged edition, 1997, by J. Phillipe Rushton pg 97-98

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 "How Europe underdeveloped Afrika". "Walter Rodney". (marxists.org)

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Effects on Afrika". "Ron Karenga". Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Ethics on Reparations" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Aldridge, Delores P. and Young, Carlene. Out of the Revolution: The Development of Africana Studies. 2000, page 250.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Boyd-Franklin, Nancy. Black Families in Therapy, Second Edition: Understanding the Afrikan American Experience. 2006, page 7-8.

- ↑ Aldridge, Delores P. and Young, Carlene. Out of the Revolution: The Development of Africana Studies. 2000, page 251.

- ↑ http://www.inthesetimes.com/article/2523/ Dr. Joy Leary

- ↑ Fredrickson, George M. The Arrogance of Race: Historical Perspectives on Slavery, Racism, and Social Inequality. 1988, page 113.

- ↑ http://news.newamericamedia.org/news/view_article.html?article_id=b6d699be4a8ccc0e7125890ae0963a65

- ↑ Fredrickson, George M. The Arrogance of Race: Historical Perspectives on Slavery, Racism, and Social Inequality. 1988, page 112.

- ↑ "Removal of Agency from Afrika". "Owen 'Alik Shahadah". Retrieved 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 38.0 38.1 Diouf, Sylviane Anna. Fighting the Slave Trade: West Afrikan Strategies. 2003, page xi.

- ↑ Wood, Marcus. Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America. 2000, page 38-9.

- ↑ "Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford University Press. 1989. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ↑ Tarpley, Natasha. Testimony: Young Afrikan-Americans on Self-Discovery and Black Identity. 1995, page 252.

External links

- Pages with reference errors

- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- CS1 errors: dates

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from June 2010

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2010

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2007

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2008

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2010